Robert Hartle worked as a Senior Archaeologist on the MOLA Headland excavation of St James’s burial ground, Euston, on behalf of Costain Skanska Joint Venture (CSjv) and HS2.

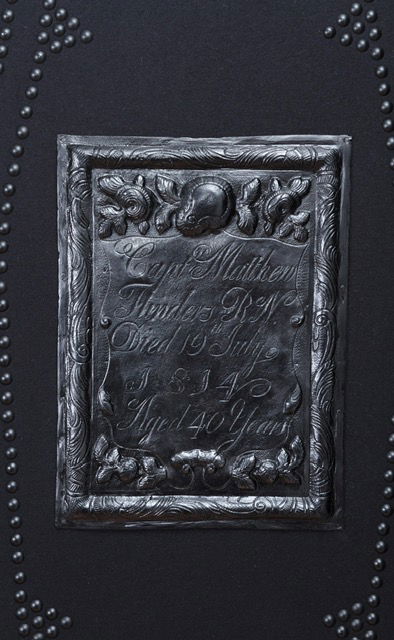

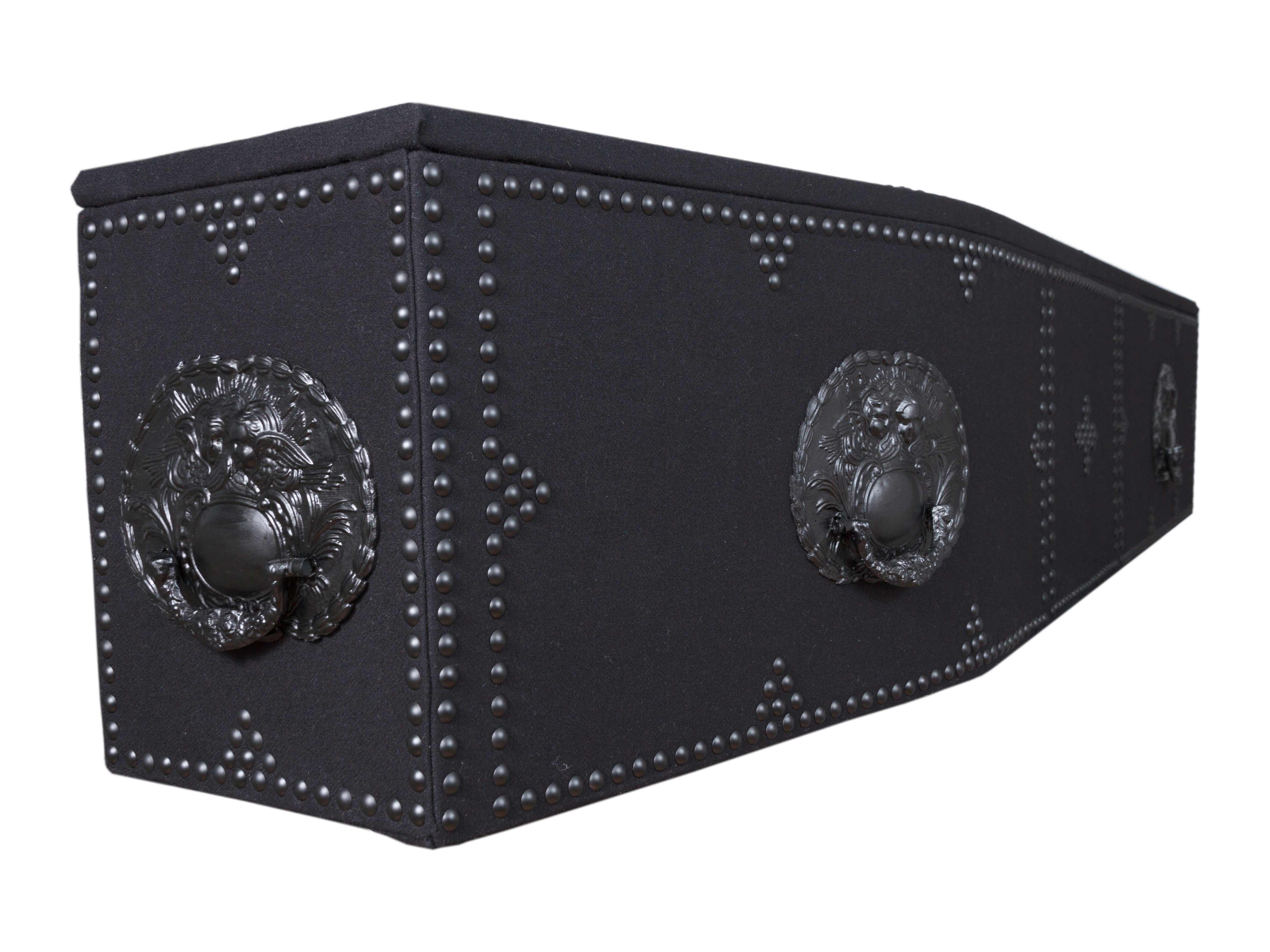

Robert examines the burial of Captain Matthew Flinders, based on archaeological and documentary evidence, and describes why and how he set about trying to make a replica of Flinders’ coffin - the centre piece of his reburial.

photo Paul Braham

The excavation of the burial ground of St James’s (in use 1789 to 1853) was an extraordinary opportunity to study contemporary life and death in London, since it contained thousands of individuals from all walks of life; men, women and children, paupers and nobility, artists and musicians, soldiers and sailors, inventors and industrialists (https://molaheadland.com/why-do-archaeologists-get-excited-by-named-burials/).

However, in January 2019, one individual’s burial which I helped identify and excavate received international interest - that of Captain Matthew Flinders.[1]

[1] Flinders is also notable to archaeologists because his grandson, Sir Flinders Petrie, the British Egyptologist, pioneered the systematic methodology which forms the basis of modern archaeology.

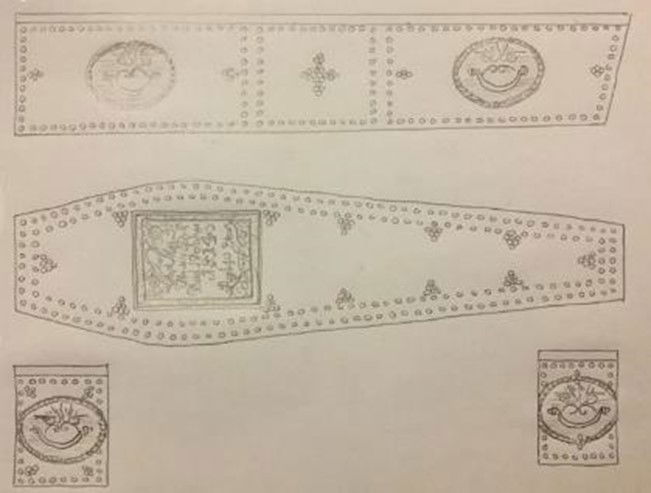

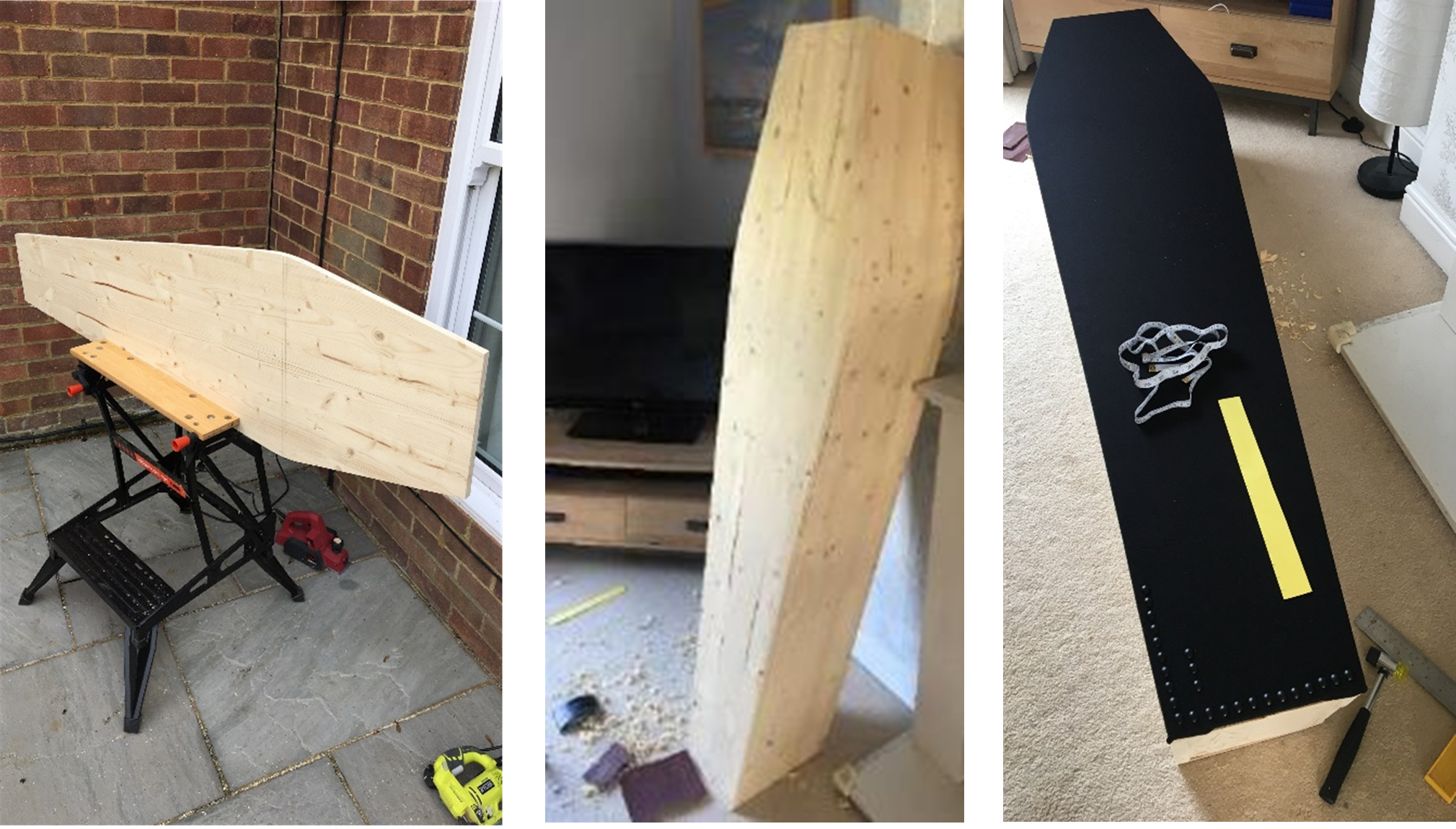

Fast forward several years and plans were announced for Flinders’ reburial in Donington, Lincolnshire. Reading the BBC’s report (https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-lincolnshire-66405752), a thought struck me; wouldn’t it be wonderful for Flinders to be reburied in a replica of his original coffin?

This was swiftly followed by another thought; I could make it. So, with a plan forming in my mind, I contacted the church of St Mary and the Holy Rood, Donington, and offered my expertise and labour. After a flurry of emails back and forth, the church and the Flinders family happily accepted my proposal and I set to work.